‘For Colored Girls’ Embodies Accessibility In Movement

Image Description: Show banner for For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf on Broadway. Credit: For Colored Girls Broadway

By Arielle Dance, Content Writer at Diversability

Content Warning: Suicide, Pregnancy

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf is a fierce and striking play based on poems by Ntozake Shange. The current production, directed and choreographed by Camille A. Brown, is nominated for 7 Tony Awards.

On Sunday, May 22, 2022, I joined my fellow members of the North Jersey Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. on a journey into New York City for the Sunday matinee of ‘For Colored Girls’. After reading Shange’s book of poems in college and seeing the Tyler Perry film adaptation, I was overwhelmed with excitement. A college classmate was in the cast and a sorority sister as a producer, so I already felt a deep connection to this historic body of art.

As a black disabled dancer and lover of all-things Broadway, I was captivated by what I experienced on the stage that Sunday. I expected to be entertained, to stare in awe and wonder, I even expected to cry… but I did not expect to feel so deeply exposed and revealed. I did not expect to see myself on stage— embodied by the Lady in Purple.

the weaving of two visual languages

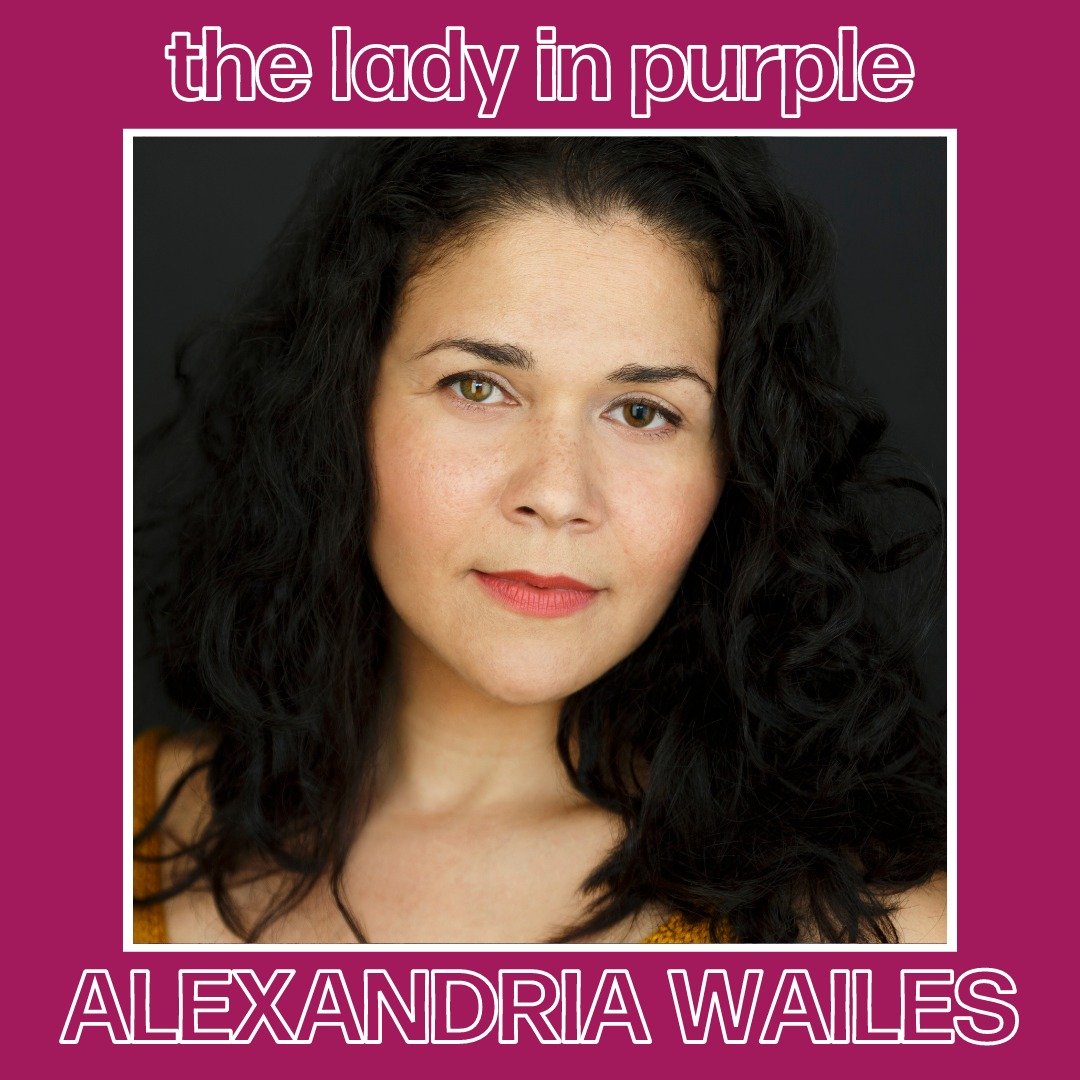

Image Description: Purple frame with headshot of Alexandria Wailes. Text on top is “the lady in purple” and at the bottom is her name. Credit: For Colored Girls Broadway

Then, Alexandria Wailes signed her first line as the Lady in Purple. Throughout the show, Wailes, a deaf, mixed race, dancer, embodied American Sign Language (ASL) from head to toe. Although Wailes primarily signed the majority of her lines, she also verbally spoke in conjunction with ASL. Let me clarify for my fellow Broadway lovers — this was not the ASL specific performance that most shows have during their run; this was a principle character who is deaf and signed her lines, lyrics, and movement.

The show hired a production director of ASL, “Ms. Wailes worked with Onudeah Nicolarakis…to focus on making sign and spoken language work together, as well as imbuing the choreography with expressiveness and nuance.” A brilliant addition that was displayed in every movement and moment.

From playful ensemble scenes of girlish rhymes, “Mama’s lil baby loves shortnin bread”, to a spellbinding monologue of love, Wailes dancing and signing paired in a captivating way. The Lady in Purple’s primary monologue was fully signed and danced by Wailes with voice over by fellow cast member, Amara Granderson (Lady in Orange). According to the New York Times, “Wailes narrates the story of a mixed-race dancer who performs the role of an Egyptian goddess of love. The production’s director…was impressed with Ms. Wailes’s elegant weaving of two visual languages, dance and A.S.L.” Each sway and gesture was accompanied by leg extensions and arms outstretched. Seeing Wailes in motion was a representation of a community… our disabled community.

The experience was amplified when fellow cast members joined in by signing at various points in the play. They were not meant to translate her words but to communicate with her, to echo her, and share in a moment with her. In a scene when each character shares “my love is too _____ to have thrown back on my face”, they each sign their expression.

“my love is too delicate to have thrown back on my face

my love is too beautiful to have thrown back on my face

my love is too sanctified to have thrown back on my face

my love is too magic to have thrown back on my face

my love is too saturday nite to have thrown back on my face

my love is too complicated to have thrown back on my face

my love is too music to have thrown back on my face”

― Ntozake Shange, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf

Wailes line, “my love is too sanctified to have thrown back on my face”, was fully signed. The audience was silent, curious of what her love was, unable to interpret ASL. Until the rest of the cast exclaimed in unison “sanctified!”. This scene transitioned into a dance with the signs for each expression: delicate, beautiful, sanctified, magic, saturday nite, complicated, and music. Before I realized it, there were tears on my face— a mix of acknowledging what my own love is and seeing it embodied in a relatable way.

Throughout the remainder of the show, ASL was utilized meticulously. Wailes and fellow cast members signed about sisterhood keeping them together through turmoil and signed about being sick of hearing their partners express “I’m sorry” when they don’t mean it. I was in awe of the melding of full body expression of ASL into a play that is rooted in call and response.

the recovery (or so I thought)

Image Description: Camille A. Brown kneeling on stage. Black woman in denim shirt, gold hoop earrings, orange head-wrap in high bun, hands on lap. Credit: Susan Pope

After the show, we were invited to a short panel discussion and talk-back. I was hoping to ask Brown about her choice to incorporate ASL in the choreography. I sat in my seat wondering, How did she take some of the smaller hand gestures and turn them into full-body movements? Was the choice hers or authentic decisions by Wailes? How did Brown know when and how to pull in the other cast members in signing or voice-over? Unfortunately, we did not have an opportunity to ask questions of the panelists.

We scurried outside for pictures and autographs; my anxiety was sky high. I knew I wanted to ask someone in the cast about this accessible incorporation of work but thought I’d missed my opportunity. My spouse reminded me of one of my favorite quotes from my own book, “be brave even when you’re scared”. With those words in mind, I moved towards the person who could answer my questions best.

Image Description: Arielle Dance (lavender shirt, black pants) on the left speaking to Camille A. Brown (denim top, gray shorts) outside of Booth Theater. Credit: Faith Edgar

I approached Camille A. Brown on the side of the Booth Theater, apologetic for taking up more of her time. I asked her about the choice to incorporate ASL and a deaf actress. She spoke in beautiful waves of wonder and all I could think about was the fact that I didn’t record this moment or have a notebook! I reminded myself to breathe, blink, smile, and nod.

Slowly, I began to register and capture pieces of her magical response. Brown spoke of the necessity for elevating the visibility of the deaf community and incorporating sign language into movement. She also explained how it was so organic to welcome the other cast members into the world of ASL to avoid Wailles being othered; embracing them into her world. The incorporation of ASL into full body movement was necessary to amplify the lived experiences of all the cast members and witnesses of the play.

Days later and I still feel like I am on a high from the experience of For Colored Girls. The raw emotions of the art mixed with the opportunity to see myself on stage (a black disabled dancer) was far more than I anticipated for a Sunday afternoon. With the Tony Awards approaching and only days remaining of For Colored Girls on stage, I feel weepy. My hope is that this show is honored for the groundbreaking work they have done. For calling the stories of black women to the forefront, for the earth shattering performance of pregnant cast member Kenita R. Miller, and especially for the elevation of the deaf community in a fully embodied performance by Alexandria Wailes.

. . .

About the author:

Arielle Dance, is a Content Writer at Diversability who identifies as a black queer woman with disabilities. A PhD in Mind-Body Medicine, Arielle is published across multiple online platforms and has a children’s book, Dearest One, that focuses on mindfulness and grief.